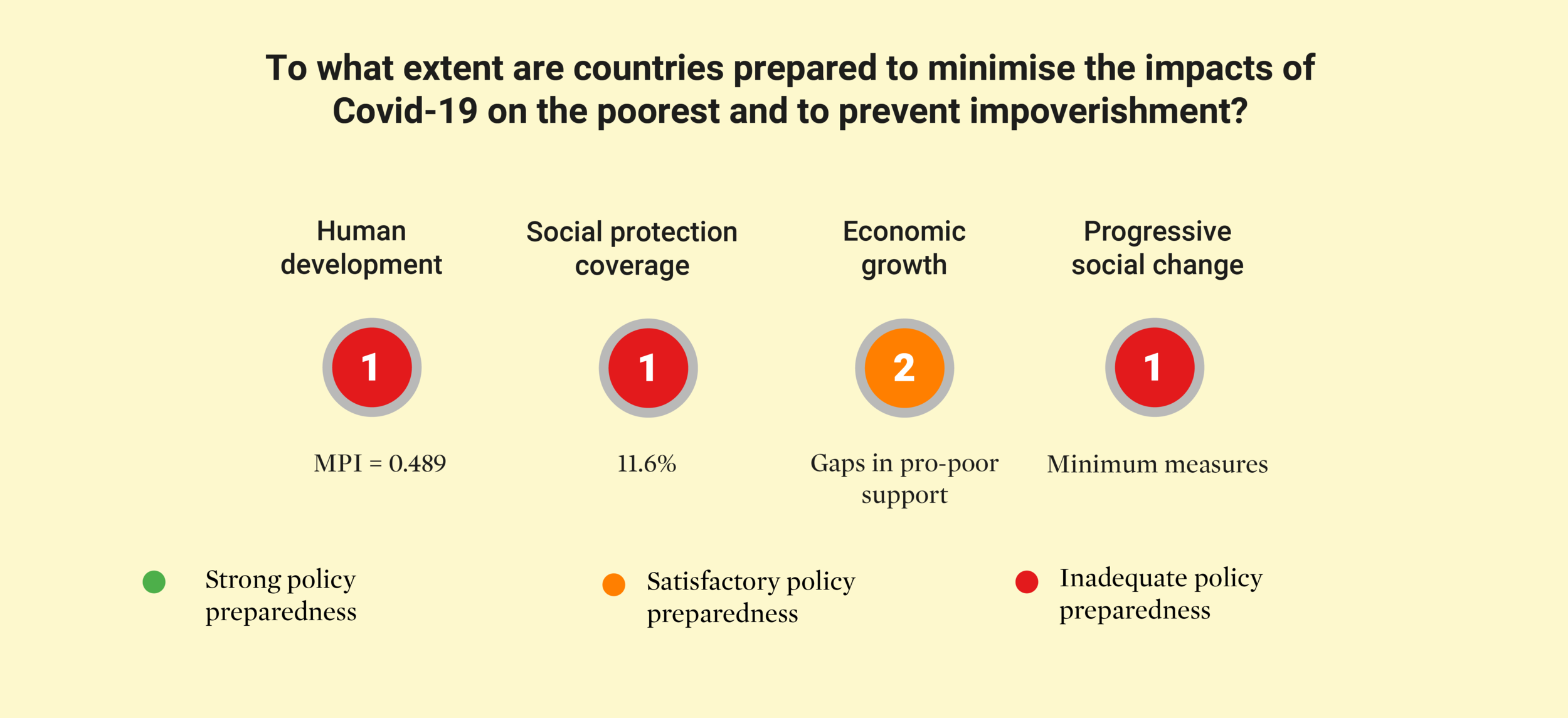

How is Covid-19 impacting living in, or at risk of, poverty in Ethiopia? What policies are needed to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 on chronic poverty? CPAN’s Covid-19 Poverty Monitor is an ongoing research project that interviews people about their experiences of the pandemic. This is the third bulletin on Ethiopia; please see the April bulletin and August bulletin, or to find out more about the project, visit our blog about the global project. This bulletin dives into the main economic, health, food security and other concerns of those interviewed, as well as how prepared the government is to minimise the impacts of Covid-19.

Areas of concern for the poorest and potential impoverishment

Persistently high cost of staple goods: As in previous rounds, the heightened price of staple goods, particularly food, is high among people’s immediate concerns. Many respondents consider these price increases to have been initially driven by market closures and transportation disruptions due to Covid-19 earlier in the pandemic, but most observe that these restrictions have been lifted and prices have not only remained high but continue to rise.

Several factors are likely to be driving increases in food prices, including tightened export availability of some commodities globally, depreciation of the country’s currency, poor harvests and trade disruptions due to conflict.

“The price of goods and services has increased since we last spoke, which creates a problem for the household. For instance, the price of a quintal of maize has increased from birr 1,500-1,800 ($31.66–$38.00)to 2,500 birr ($52.79) [All currency conversion as of 10 November 2021 from www.xe.com]. The price of other goods such as salt, coffee beans and related shop products has dramatically increased. I am just struggling to support my family given the skyrocketing price of goods and services. We live a hand-to-mouth life.” Female respondent, SNNP, 25

“Since we spoke the household expenditure has increased due to the increase in market prices. For instance, the price of food oil has increased from 15 birr ($0.31) per bottle to 40 birr ($0.84) now. The coffee beans that used to be bought for 60 birr ($1.26) per kg increased to 100 birr ($2.11) per kg. Similarly, rice, spaghetti and other shop products have dramatically increased and keep on increasing from day to day. For example, the price of spaghetti has increased from 17 birr ($0.35) to 30 birr ($0.63).” Female respondent, SNNP, 33

“We thought that the price increment was because of Covid-19, but since nobody is ill and the pandemic did not reach here, the price increment by itself might not be related with Covid-19. We do not know what is happening from above [government], but here we cannot attribute all to the corona.” Female respondent, Amhara, 35

Concerns over the impact of Covid-19 on health are low: All respondents report that concerns over the direct health effects of Covid-19 have diminished significantly in their communities. While health centres are reported to be maintaining Covid-19 protocols and advising mitigation measures, there is a general sense in all the communities sampled that Covid-19 has either left or never reached them. Alongside this general sense that Covid-19 is no longer a risk, other risks such as climate change and conflict feature higher on people’s lists of concerns (see below). Covid-19 has been deprioritised by most even though vaccination programmes have not yet reached these communities.

“Issues related to hygiene and sanitation are completely forgotten. People give more focus on finding a mechanism to get income and to feed their families rather than focusing on Covid-19. Health professionals also stopped awareness-raising except when we go to the health centre. People believe that there is no Covid-19, or it was already prevented.” Male respondent, Oromia, 60

“What do we know, if they tell us to be careful, we accept their warnings, and if they remain silent, then we do not care about it.” Female respondent, Amhara, 40

“We focus more on how to feed our children and to prevent them from dying from hunger rather than thinking about Covid-19.” Female respondent, Oromia, 41

“I don’t use a facemask if not I am obliged. It is because if you use a facemask, you are considered snobbish. If somebody wears a mask, people will see him as if acting like as a superior.” Male respondent, SNNP, 37

Mixed vaccine awareness and willingness: All respondents were asked about their knowledge of Covid-19 vaccines and their willingness to accept a vaccine if offered one. There were mixed levels of awareness of vaccines with many people aware that they existed but little information beyond that. Among those aware of vaccines, all observed that there were no vaccines available in their area. There were also mixed responses in terms of respondents’ willingness to accept the vaccine. Some stated clearly that they would accept it if offered, others gave more vague responses as to their willingness to accept, while some stated they would not accept the vaccine.

“There is no information about the Covid-19 vaccination. I heard that last time the woreda [district] officials in the area were vaccinated but I couldn’t get the vaccination. However, now there is no information about the vaccination.” Male respondent, SNNP, 37

“Now people talk on media about vaccination, but vaccination is not important in the absence of the pandemic. Vaccination is needed if there is an illness in the area but there is no coronavirus and we do not need the vaccination.” Female respondent, Oromia, 45

Heightened food insecurity: Nearly all respondents reported heightened food insecurity since the last round of interviews. In most cases, this insecurity was attributed to the high price of food (noted above), with some also attributing it to lower than normal agricultural yield due to the drought and locust infestations. Some respondents report eating only two and in some cases one meal per day and in nearly all cases respondents have cut out certain goods from their diet or switched to lower quality alternatives.

“The food shortage is so critical at my household. Only the smaller children can eat three times per day. Sometimes, they may not eat three times. There are times when they eat only once a day.” Female respondent, Oromia, 41

“We cannot buy the maize crop because it is so expensive it reaches 2,800 birr ($59.07) per quintal. This is unthinkable for poor households like ours.” Male respondent, Oromia, 46

“There is a critical shortage of food in my family. We have no livestock or income. We are dependent on income obtained from the sales of sugar cane that my children are engaging in. The price of maize in the market is very expensive. Previously we ate three times a day but now due to shortage of food and income we eat only once, and we could not get quality food.” Female respondent, Oromia, 45

“We have sold more crops that we have kept at home for consumption to cover the increasing household expenditure and buy shop products. Moreover, we have reduced the amount of food we have consumed to minimize our expenditure.” Female respondent, SNNP, 33

Concerns around climate change: Most respondents continue to reflect on the effects of drought earlier in the season and the knock-on effects on livelihoods and food security. Although there has been some relief with the recent rains, it did not appear to lead to a full recovery of crops. Some farmers have been able to harvest later season crops such as haricot beans. Many respondents continue to list climate-related impacts on agricultural production as a leading cause of livelihoods losses and food insecurity.

“The summer rain was good. This has a positive impact on agricultural production. Especially the maize and haricot beans have been growing very well. This has brought hope for many of us. The last week has been very good in terms of the amount of rain.” Male respondent, Oromia, 71

“The teff crops which suffered from the shortage of rainfall during May/June was completely destroyed. People completely lost the belg crop this year. However, the summer rain was good for the maize and haricot beans. The rain is better for both the crops and animals during this summer. We hope that we will get a better harvest for the next harvest season.” Male respondent, Oromia, 60

Concerns around conflict: Concerns surrounding the threat of conflict that arose in the second round of interviews appear to be increasing among respondents in all sampled areas. The Amhara region has been directly affected by conflict and young people have been conscripted in Oromia. SNNP has been indirectly affected by increased prices due to conflict and households are being asked to contribute food and financial resources to the war effort.

In some cases, respondents are more generally aware of threats of conflict nearby, while others have been directly affected by relatives or community members being trained to fight. Displacement does not appear to have occurred in the areas sampled, but some respondents fear they could be forced to leave if the conflict escalates. One respondent indicated that her son joined the military since we last spoke.

“Physically active people have been taking military training to protect their communities from any insurgents. We are informed that there are conflicts in different parts of the country and the government is training the local farmers and young people to protect their communities from possible attacks from guerrilla fighters. During [community] meetings the focus is on the peace and security of the country. No issues related to Covid-19 have been raised or discussed at the meetings and trainings.” Male respondent, Oromia, 60

“We hear that people are getting displaced [due to the conflict] and our families who were closer to the war are now displaced. We fear that this may become a reality for us as well. It is frightening, there is not much supply so we cannot buy what we want. There is not much movement and transaction. People are overwhelmed by fear.” Female respondent, Amhara 35

“The market inflation is due to the war between the federal government and Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF). For the war preparation, the army needs different resources, and the community are also supporting the army in preparing foods, donating equipment, animals, etc.” Male respondent, SNNP, 37

Challenges and threats to wellbeing

Challenges faced in the last year: Respondents were asked to reflect on whether the Covid-19 pandemic was the most significant challenge to their household’s wellbeing over the last year or whether other factors were more significant. No respondents cited Covid-19 as their household’s biggest challenge over the last year, though some did reflect on the pandemic’s role in driving other challenges. The most widely cited challenge cited was inflated prices of staple goods (namely food) followed by the effects of drought and locusts on agricultural production. One respondent cited conflict as their biggest challenge over the last year and one cited lack of health insurance to deal with their family’s non-Covid related health issues.

Threats to future wellbeing: Respondents were asked to reflect on the most important issues that could threaten their household’s wellbeing over the next year. Again, no respondents cited Covid-19 as their household’s biggest concern over the next year, though some did reflect on the pandemic’s role in driving other challenges. The most widely cited concern was food insecurity, particularly with regards to the impacts of climate change, such as drought, followed by continued inflation of staple goods. Three respondents cited increased conflict as their biggest concern over the next year and one respondent cited concerns around their households’ impoverishment.

Long term impacts of Covid-19: Respondents were asked whether they thought that the Covid-19 pandemic could have any lasting effects on themselves, their households, or their communities. Many reflected on price inflation and expressed concerns that prices would not return to pre-Covid-19 levels or that effective price controls would be introduced to mitigate price hikes during times of instability.

Inflation is a major lasting effect of Covid-19 as prices have not changed since they rose earlier in the pandemic. One respondent reflected on the possible long-term impacts on education (see April and September bulletins for further details on the impacts on education), while another respondent reflected on the possibility of long term impoverishment.

Policy recommendations to mitigate the effects of Covid-19

At the end of each interview, respondents were asked to offer three suggestions for the government to help support them, their household, or their community to better cope with the lasting effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, building on what they had discussed in the interview so far. Their suggestions included:

Government controls on price inflation and broader market stabilisation

Provision of food aid

Provision of agricultural inputs including improved seeds and fertilisers and better support to mitigate climate impacts on production

Protections against Covid-19, including the provision of face masks and access to vaccines

Restoring peace and assuring personal safety

Methodology

CPAN Covid-19 Poverty Monitor bulletins are compiled using a combination of original qualitative data collection from a small number of affected people in each country, interviews with local leaders and community development actors, and secondary data from a range of available published sources. Interviews for this bulletin were conducted in August 2021 in Amhara (eight households), Oromia (nine households) and Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Region (SNNP) (seven households).

Key external sources

To find out more about the impacts of Covid-19 on poverty in Ethiopia, please explore the following sources that were reviewed for this bulletin:

This project was made possible with support from Covid Collective.

Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). The Collective brings together the expertise of, UK and Southern-based research partner organisations and offers a rapid social science research response to inform decision-making on some of the most pressing Covid-19 related development challenges.

CMI