How is COVID-19 impacting people living in, or at risk of, poverty in Zambia? What policies are needed to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on chronic poverty? CPAN’s COVID-19 Poverty Monitor is an ongoing research project that interviews people about their experiences of the pandemic. This is the first bulletin focused on Zambia - to find out more about the project, visit our blog about the global project. This bulletin dives into the main economic, health, food security and other concerns of those interviewed, as well as policies to minimise the impacts of COVID-19 suggested by the respondents.

Areas of concern for the poorest and potential impoverishment

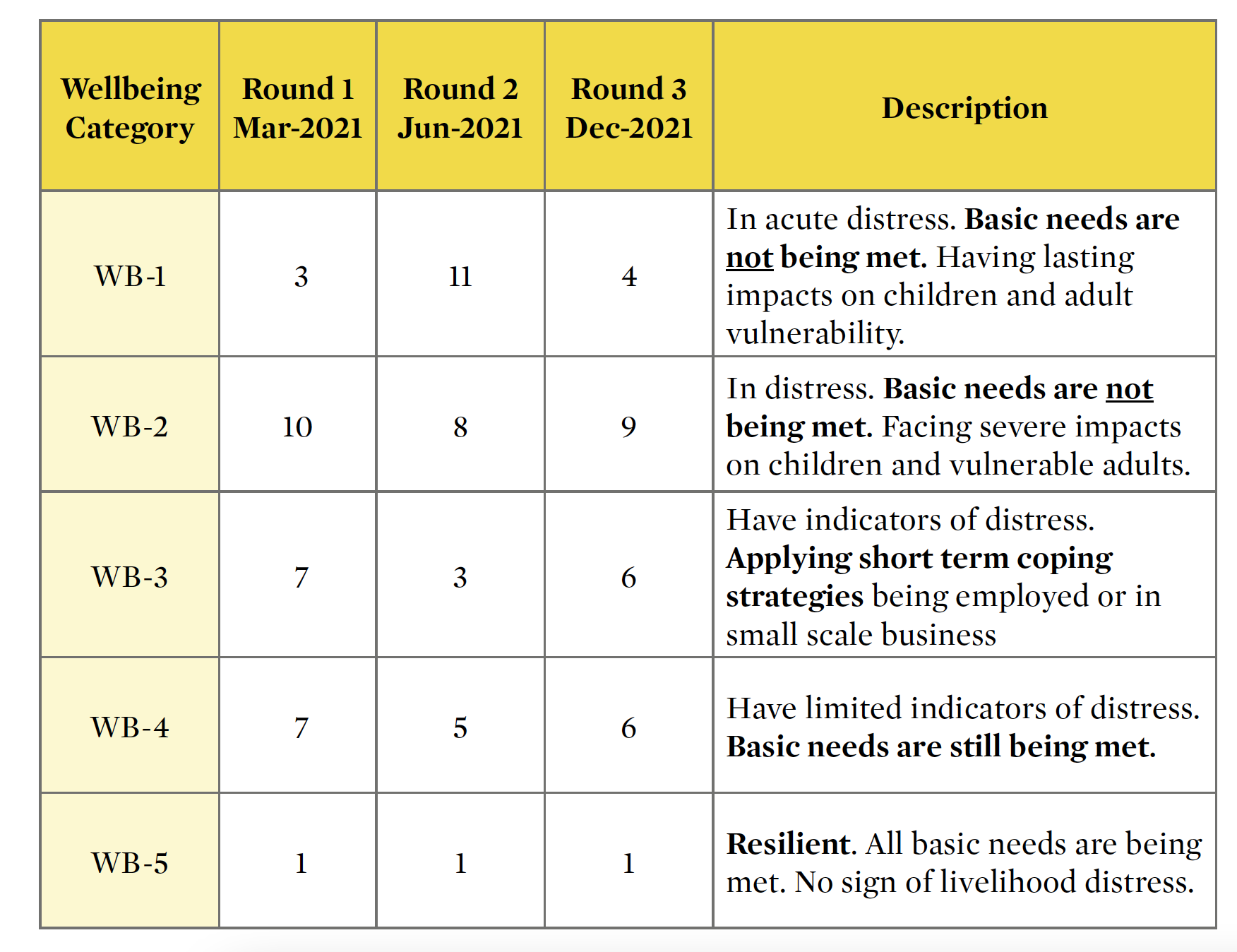

There was an increase in the number of households reporting improvement in wellbeing (WB) in November 2021 since the last interview round in June 2021 (from four to 13 households). Reported improvements in wellbeing were largely attributed to the reduced cost of doing business following the appreciation of the local currency, increased social cohesion due to a decline in COVID-19 related stigma, extension of free education to grade 12, public health insurance, and adoption of new livelihoods.

Areas of concern identified as needing attention to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 included support for business financing, jobs, livelihoods, school bursary, agriculture and health financing. There were high expectations that the new government would address the identified concerns in the short to medium term. However, all participants anticipated an increase in the cost of living due to the rise in fuel prices in December 2021.

Partial recovery: Half (13) of participating households reported partial economic recovery, about a quarter reported continued decline (7) and the rest reported no change in wellbeing (6). Some respondents that reported lost livelihoods in the previous bulletins report having new livelihood sources while others report adopting more than one livelihood (see below). Some micro and small entrepreneurs report being able to buy more goods for resale due to the appreciation of the local currency. Respondents reported a slight decline in the cost of living, which is confirmed by a recent report from the Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection (JCTR) showing a marginal decline in the cost of the basic needs and nutrition basket for a family of five in Lusaka from Kwacha (K)8,644.50 ($478.11)3 in March 2021 to K8,359.80 ($462.34) in December 2021 (all conversions as of 7 March 2022 from www.xe.com). The decline is attributed to the appreciation of the local currency against major currencies; US$1 was selling at about K23 during the first round of interviews and is now selling at K17 (19/01/2022). Annual inflation for December 2021 decreased to 16.4% from 22.8% recorded in March 2021. Prices of goods and services therefore increased by 16.4% on average between December 2020 and December 2021.

Diversification of livelihoods: Some households attributed their improved wellbeing to the adoption of diverse ways of raising incomes including micro-businesses, gardening, farming day labour and other activities.

“My wellbeing has improved. Last time you came, I only had one business but now I have two businesses. I sell charcoal and beer commonly known as Kachasu. The economy is doing fine; the charcoal is less expensive, and I have more customers because of load shedding. Electricity goes from morning till midnight sometimes and people have no option but to buy charcoal.” Female urban participant

“I have different types of livelihoods like a grocery business, farming (crops and livestock), real estate (five flats), butchery, community savings, and I am also running a depot for chicken. Having multiple sources of income has really helped improve my wellbeing.” Male urban participant

Reduced cost of doing business: Most households involved in trading attributed their improved wellbeing to reduced costs of doing business with the improvement of the local currency. This has enabled the traders to buy more stock with less money.

“My grocery business is doing well. I am now able to buy more stock because the dollar has gone down. Last time you came, K5,000 ($276.81) worth of stock was way little compared to now. The dollar was then selling at about K22, but it is now selling at K16.” Male urban participant

“The dollar is doing fine now. When we go for orders, it makes sense because we are able to order more with less money as compared to before.” Male urban participant.

Improved sales: Some respondents engaged in trading goods further attributed their improved wellbeing to improvement in their daily sales

“My wellbeing has improved because my tenants are able to pay rentals and my business is booming every day.” Male urban participant

“Last time we spoke I used to get K6,500 ($359.70) monthly from both my grocery and my rentals, now I am getting close to K10,000 ($553.39) per month because my sales have increased… the change is due to the new government, our economy is doing fine after so many years of suffering.” Male urban participant

Reduced cost of basic commodities: Most of the participants reported a decline in expenditure due to a reduction in prices of basic commodities.

“The prices at which most goods are being sold now is better and it is slowly becoming bearable, and this is making it easy for us to meet our daily basic needs. Things are now cheap and this has been the major contribution to the changes we are undergoing… farming inputs have also become affordable and this is helping us as farmers.” Male rural participant

Despite the reported improvements, most households are yet to regain pre-pandemic levels of income and wellbeing. Participants also reported a loss of income from businesses, lack of employment and limited access to start-up capital. The sustainability of the reported gains is also not guaranteed due to the possible business disruptions from further Covid-19 restrictions.

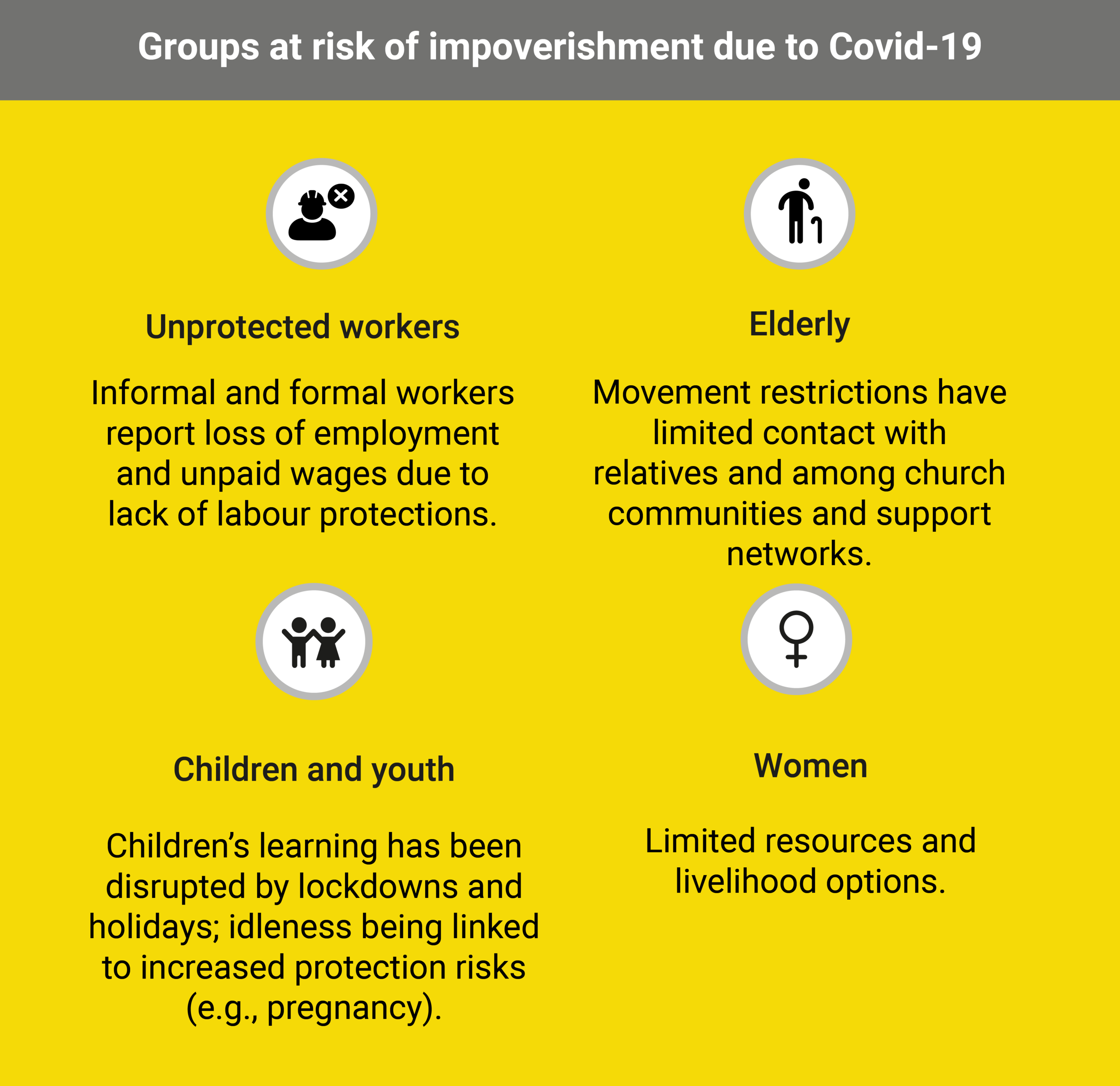

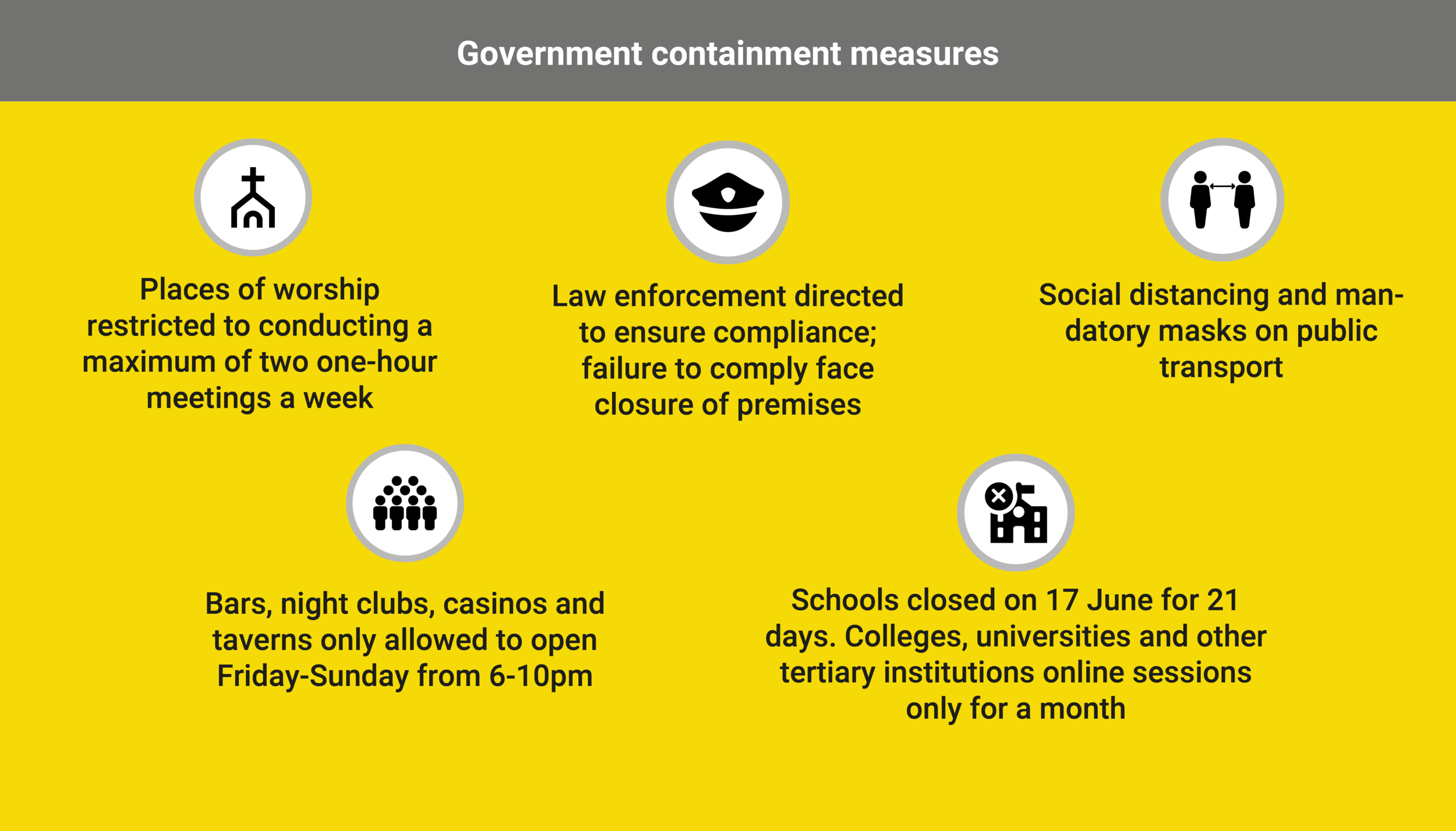

Loss of income: Zambia introduced heightened public health measures against Covid-19 again on 28November 2021. Operation of bars, taverns, restaurants, nightclubs, cinemas and stadia were limited to between 6–8pm, four times a week. These closures led to partial losses of income. Cross-border trade was affected due to the introduction of mandatory testing and 10-day quarantine for all those coming from high-risk countries. Power load shedding also largely contributed to a loss of income for businesses without backup power.

“There has been loss of income, especially from the grocery store. We used to order our merchandise cheaply from Malawi, but we can’t freely cross the border now due to Covid-19 restrictions…My bar business is also affected. I’m only allowed to operate about three days for a limited number of hours which has led to loss of income.” Male rural participant

Limited employment: Participants reported continued limited employment. Some people who had lost employment during the first bulletin in April 2021 are still unable to find employment. People are, however, optimistic that the new government will provide jobs.

Limited access to business financing: Most participants reported that they have no access to financing for start-up businesses because most micro-finance institutions go for salaried employees. The participants reported that lack of access to finance limits their ability to start and sustain new livelihoods.

“Our wellbeing is very bad and this situation we are in is due to a lack of capital. I would like to do business, but I do not have capital. Banks and other lending institutions only lend to those who are working. Kaloba (informal credit offered by moneylenders) is available, but the problem is that they want collateral that we do not have, and they charge very high-interest rates which are not good for a start-up business.” Urban female participant

Case study of Elias

“There has been a decline in my wellbeing… Right now, nothing is making sense for me. My barbershop business is almost collapsing, power goes from morning till evening, sometimes from morning till 4pm and that’s when I open the shop. When you open customers don’t come. My rentals for the shop are due and I am four months behind… It is a struggle for me to eat…I wait for a good Samaritan to give me something. For example, I drink beer and my friends call me to go and drink with them. I will escort them and tell them to give me the money for my beer and buy food. My friend will give me a K5 then I will buy K2 buns, K2 sugar, and I will save K1 for the next day. That’s how I survive.”

Table 1: Change in wellbeing of participants between rounds 1 and 2 of interviews

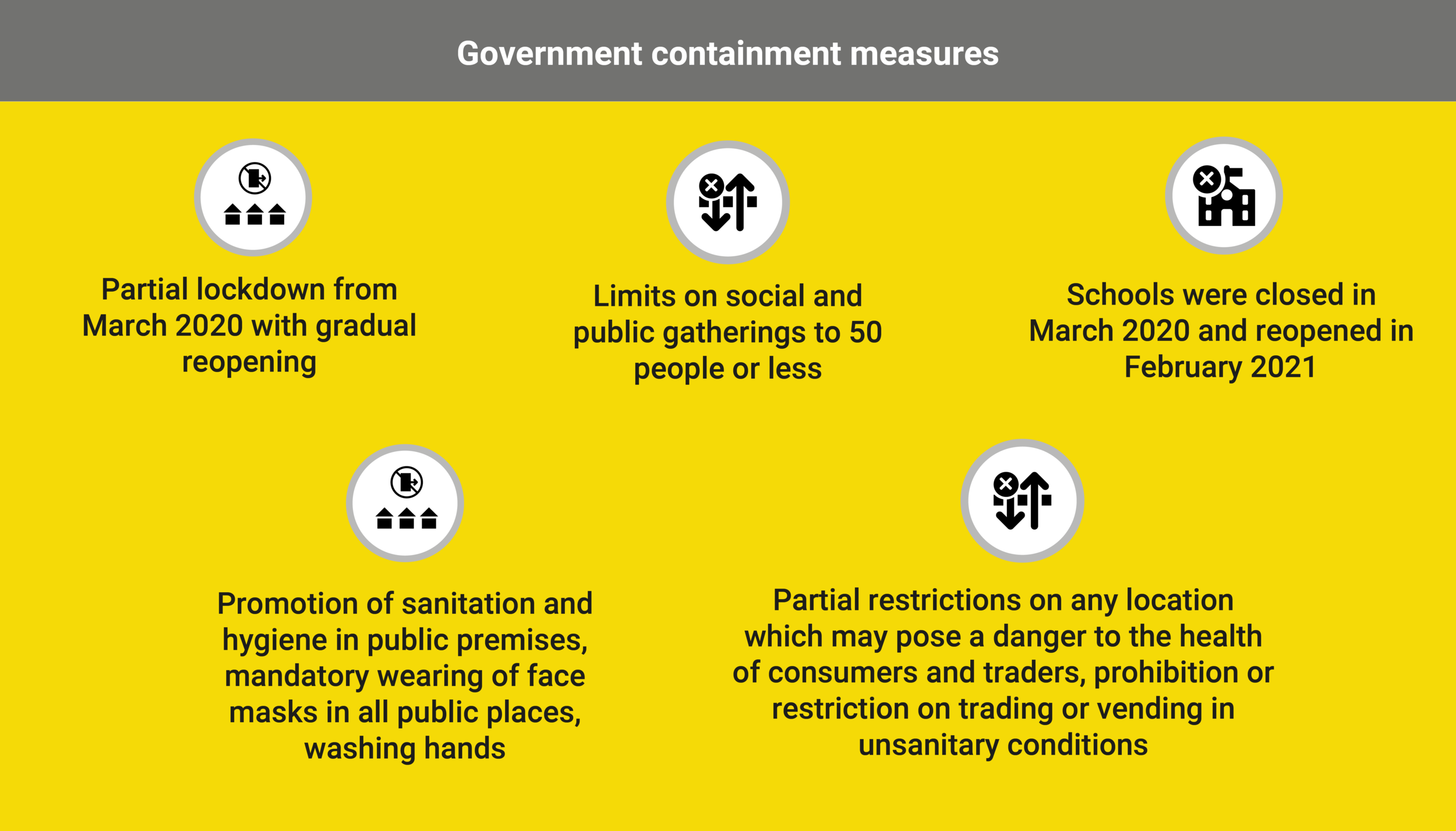

Partial recovery: All respondents acknowledged a reduced impact of COVID-19 on education since the last bulletin (August 2021). Physical classes were maintained since the last bulletin although most participants confirmed that pupils were behind due to previous closures.

Extension of free education to high school and pre-school: The new government extended free education from primary school (grade 1 to 7) to high school (grade 8 to 12) and pre-school in all public schools. This provided an opportunity for those who had dropped out of school due to financial challenges to re-enrol.

Limited capacity/infrastructure for virtual learning: The government called for colleges and universities to increase provision of online lessons following the outbreak of the Omicron variant. Virtual learning is however less accessible for learners in remote and rural areas with limited connectivity. Public schools are also ill-equipped to effectively apply virtual learning modalities due to limited virtual learning infrastructure owing to limited resources.

“Online learning is a good approach in the era of COVID-19, but the challenge is that learners, especially those in remote rural areas are faced with poor internet connections and limited access to digital devices.” KII participant

Extension of school holiday: The government postponed the reopening of primary and secondary schools by two weeks (from 10–24 January 2022) due to a surge in COVID-19 cases following the emergence of the Omicron variant of Covid-19. The holiday extension was also meant to allow for more school-going children to get vaccinated.

Case study of Hope

Hope is a 17-year-old girl who dropped out of school in 2021 due to lack of financial support. Her parents divorced and she lives with her grandmother. Her parents are unable to sponsor her school fees and her grandmother failed to take her back to school after the initial COVID-19 partial lockdown. Hope unsuccessfully tried to raise school fees by selling cooked chicken pieces. She couldn’t save from her sales because most of the income was being used for subsistence at home. Hope has now re-enrolled in school because the government has extended free education to public secondary schools.

Access to health services: COVID-19 constrained the health system and led to limited access and utilisation of other health services. Some participants reported that the promotion of home-based management of non-critical cases COVID-19 has considerably relieved the health system although there is concern that this may be contributing to fatalities from COVID-19.

“The increase in home-based management of mild to moderate cases of COVID- 19 appear to have greatly relieved the health system and shifted resources to other health needs that had previously been neglected due to focus of resources on COVID-19. However, this may have contributed to [fatalities from] COVID-19.” KII participant

Covid-19 vaccination: There are still mixed feelings regarding the COVID-19 vaccine through the national turn-out for vaccination has improved from the last round of interviews from about 1% to about 8.5% (9 August 2021 to 17 January 2022). The government has also extended coverage of COVID-19 vaccinations to children aged 12 years and above.

“I will not be going for COVID-19 vaccinations because I prefer natural remedies. I take them and they are working well for me, but I can advise the people to take the vaccine because the Ministry of Health is saying it is good for everyone including children.” Male urban participant

Poor health is a major driver of descents into poverty because it reduces productivity and draws on limited income and/or savings. This was reaffirmed by a key informant in the context of COVID-19 in Zambia:

“Poor health pushes people and households into poverty by reducing household income through high medical expenses and, for those in the informal economy whose incomes depend on labour supply, by reducing household income from work. This exposes individuals and households to a dual challenge that leads to heightened poverty.” KII participant

National Health Insurance: Zambia has an inclusive National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in place which covers all people regardless of socio-economic status. The scheme provides for free access to health services for all Social Cash Transfer (SCT) beneficiaries, retirees, elderly (above 65 years), and people with disabilities. The scheme is however faced with financing challenges owing to the low proportion of beneficiaries who contribute and the low size of the premium each person contributes.

“The NHIS is a means of harmonising funding into the health system by having premiums collected based on ability to pay from all eligible citizens and legal residents, with exemptions and subsidies for the vulnerable, older people [above 65 years], and the mentally and [people with mental and physical disabilities].” KII participant

Social cohesion: The outbreak of COVID-19 led to a decline in social cohesion. Many participants now report increased social cohesion which has in turn improved informal support networks. The participants further report that the improvement in the informal support system has contributed to improvement in people’s psychosocial and economic wellbeing.

Stigmatisation: Patients and survivors of COVID-19 continue to face stigma and discrimination. Stigma has the potential to undermine social cohesion and prompt social isolation of groups. The social isolation or rejection that comes with stigma has the potential to negatively impact their psychological, economic and social wellbeing. COVID-19 related stigma is hence associated with a descent into poverty.

“I tested positive for COVID-19 in September 2021 and luckily, I was able to fully recover after two weeks of hospitalisation. The community stopped buying groceries from my makeshift shop because they were scared of contracting the virus. Even my close friends stopped interacting with me long after I got well. That is how my business went down and eventually collapsed.” Male urban participant.

“I had COVID-19 a month ago (October 2021). It was not serious but when people learnt about this, they stopped visiting me or greeting me on the road. This has really affected my wellbeing because I totally depend on support from the community and now the people that usually help me are avoiding me.” Female urban participant

Delay in delivery of farm inputs: Rural households that rely on fertiliser and inputs. Farmer Input Support Programme (FISP) reports continued delay in government disbursement of fertiliser and other farm inputs. Some farmers report not receiving the inputs by the onset of the rain/wet season, making it likely that these delays will affect crop yields.

Climate change: The 2021/2022 farming season has been characterised by delays in the onset of rains, prolonged dry spells after the onset of rains as well as flash floods due to above-normal rains. Most farmers that planted during the first rains lost their crops due to the dry spells that followed while others lost their crops to flash floods. The government and its partners, through the Disaster Management and Mitigation Unit (DMMU), have been providing relief in form of input replacement and shelter in affected areas.

“There is a disaster of the loss of crops for the farmers who planted during the first rains (Mid-November 2021) due to prolonged dry spells being experienced, people are having to replant. Peasant farmers are most affected. DMMU is working on facilitating their access to early maturing seed.” KII participant

Fall armyworms: Zambia announced the outbreak of fall armyworms on 6 January 2022, after interviews were conducted. The country has experienced outbreaks of fall armyworms in seven of the last 10 agricultural seasons. These migratory armyworms are a great threat to the country’s food security. The government has strengthened surveillance and other control measures to contain the infestation of migratory pests.

Coping Strategies

Government support in form of social cash transfer, health insurance, subsidised farm inputs, free education and pensions.

Engaging in new livelihood activities including casual labour, informal trade, gardening and farming.

Social cohesion: Informal support networks including family, friends and well-wishers.

Savings and borrowing: A few participants who are resilient report being able to save during good times and draw on savings or borrow during hard times.

Limiting expenditure to essential commodities, buying essential commodities from cheaper sources and food rationing.

Adherence to Covid-19 guidelines and vaccination is seen are seen as coping strategies because they help avoid bills that come with COVID-19.

Prayer: Some report that they pray and wait for God to provide.

Policy Recommendations

These were made by respondents:

There is a need for the government (through the new Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises Development) to come up with a transparent and credible mechanism for supporting micro and small enterprises by providing financial, material and technical support as well as creating a conducive environment for these enterprises.

There is a need to scale up sensitisation activities against the stigmatisation of patients and survivors of COVID-19.

There is a need for timely disbursement of grants for schools to ensure the success and sustainability of the increased scope of free education.

Decentralise the Disaster Management and Mitigation Unit (DMMU) to a level where each district can have a disaster preparedness plan that is unique, and tailor-made to its own context.

Strengthen the institutional framework and capacity of the government of Zambia in social health protection through the successful implementation of the National Health Insurance Scheme, thus strengthening the healthcare financing landscape in Zambia.

Accelerate the extension of national health insurance coverage to the informal economy which accounts for about 80% of the workforce.

Enactment of access to information legislation to allow for easy monitoring of government expenditure by civil society organisations and other stakeholders.

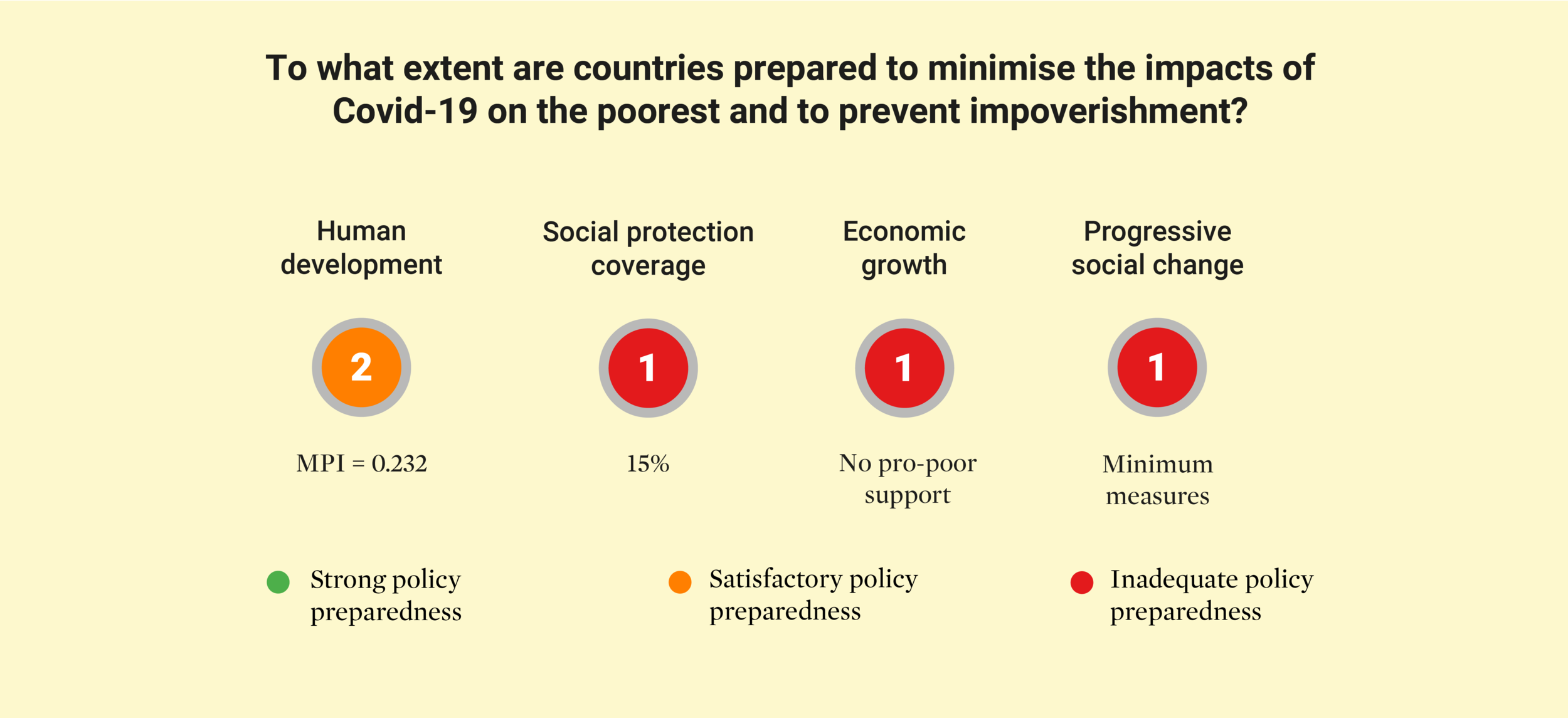

Programmes in place to mitigate impoverishment due to COVID-19

Public health insurance: The government provides contribution-based universal health insurance exempts the vulnerable from paying. Provision of free health services to the poor helps lessen the economic burden that comes with COVID-19.

Income: The government provides financial support to the vulnerable and non-viable people in society through the Social Cash Transfer (SCT) Scheme. Respondents reported receiving the SCT, and those who don’t are optimistic about receiving it in future.

Nutritional security: The government provides food security through FISP and Food Security Packs.

Emergency support: The government through DMMU provides relief to the poor in times of emergencies. DMMU further sensitises communities on emergency preparedness which enhances resilience in times of shocks. Flash floods and armyworms occurred after the household interviews had been completed, illustrating how ongoing emergencies are in Zambia.

Free education: The government is currently providing free education in all public day schools from nursery to secondary school. The government further provides bursaries for tertiary education in some public institutions of higher learning.

Methodology

CPAN country bulletins are compiled using a combination of original qualitative data collected from a small number of affected people in each country, interviews with local leaders and community development actors, and secondary data from a range of available published sources. Interviews were conducted with 26 households for this bulletin between November and December 2021. The households included six urban households from Lusaka, eight peri-urban households from Kabwe and twelve rural households. Five national-level key informant interviews were also conducted between December 2021 and January 2022.

Key external sources

To find out more about the impacts of COVID-19 on poverty in Nepal, please explore the following sources that were reviewed for this bulletin:

This project was made possible with support from Covid Collective.

Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). The Collective brings together the expertise of, UK and Southern-based research partner organisations and offers a rapid social science research response to inform decision-making on some of the most pressing Covid-19 related development challenges.