Thank you for visiting our new Covid-19 Poverty Monitor. To find out more about the project, visit our blog about the project.

Areas of concern for the poorest and potential impoverishment

Loss of income from businesses: Zambia went into a partial lockdown when it recorded the first cases of Covid-19 in March 2020. Some micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) such as bars, cinemas, lodges, hotels, saloons and barbershops were completely shut down while other MSMEs were allowed to operate with restricted hours and conditions. Non-essential foreign travel was discouraged. The easing of lockdown measures was phased with bars being the last open on a government-controlled schedule. Some people who were running micro and small enterprises before the partial lockdown said they were unable to resume operations after lockdown measures eased as they had spent all their money during the partial lockdown, costs of doing business have increased and/or reduced volume of customers due to fears of Covid-19. All MSMEs who managed to resume operations report a decline in revenue.

Those involved in cross border trade report difficulties in conducting business due to additional Covid-19 restrictions at the borders which are exacerbated by the continued depreciation of the local currency (Zambian kwacha) against the US dollar and other major currencies: the kwacha weakened by about 9% between September 2020 and February 2021. The majority of people also report cautious and limited patronage of business places due to fear of contracting Covid-19, which has further reduced the income of MSMEs. Loss of business income is common in both urban and rural areas.

Case study of Elias

Elias is a 50-year-old micro-entrepreneur currently running a barbershop in one of the shanty compounds of Lusaka, the capital. He is disabled (walks with aid). He reports doing relatively well before the Covid-19 outbreak. He was married and sold cigarettes before the partial lockdown while his wife was a tailor. Elias used up all his capital for the cigarette business for subsistence during the lockdown. He resumed his barbing business after the partial lockdown, but business was very slow as people were still scared of contracting Covid-19 and there was a lot of power load shedding. He bought a battery and inverter for power back up, but his battery was later stolen. He reported that his wife divorced him on account of not having enough income to take care of her during the Covid-19 period and he moved into a rented two-roomed house with his son. He barely keeps up with his rentals. His business is still not doing well as people are still scared of Covid-19 so he relies on his close friends for business. His main coping strategy is reducing the number and quality of daily meals.

Loss of employment: Some people report losing employment during the Covid-19 partial lockdown and very few of them report being rehired by their employers after easing of the partial lockdown. Loss of employment is common in urban areas and often leads to failure to maintain rented accommodation and provide food and educational support for their children.

“I know a lot of people who lost jobs during the lockdown and very few of them got rehired after the partial lockdown was lifted. I would say maybe two out of 10 got rehired. Otherwise, we now have so many loafers and beggars. Covid-19 has come with so many difficulties.”

“I have five flats which are rented out. The challenge is that three of the tenants lost employment due to Covid-19 and they have been defaulting because they don’t have other sources of income, they owe ZK17,000.”

Poverty pathways key:

Chronic Poor (CP): those who have remained poor for at least 5 years.

Temporary Escapers (TEs): those starting off as poor five years prior to the study and later escape poverty and fall back into poverty.

Sustained Escape (SE): those starting as poor and later have a sustained escape from poverty (including those starting off as non-poor and sustain or increase their status.

Increased cost of basic items: All people report an increase in cost of essential food and non-food related items, including healthcare. This is in line with the Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection’s (JCTR) reported increase in the cost of the basic needs and nutrition basket from ZK7,158.67 in April 2020 to ZK8,394.01 in January 2021. The increasing price of commodities is largely attributed to the continued depreciation of the local currency against major currencies; US$1 was selling at ZK14.9 before reported cases of Covid-19 in Zambia (29/02/2020) and is now selling at ZK22.6329 (22/03/2021). The annual inflation rate increased from 14% in March 2020 to 22.8% in March 2021 mainly due to price increases of both food and non-food items; prices of goods and services increased by about 22.8% during this period.

“Everything has become expensive for example one tomato is costing ZK2, imagine that. Cost of living has become high.”

“My wellbeing has gone down because cost of living has gone up. My wellbeing has not improved, am still doing the same business (selling charcoal) I have been doing for so many years… I am getting poorer every day because the cost of commodities keeps increasing without a corresponding increase in my income.”

Loss of remittances: Some chronically poor people (CPs) who survived on remittances from family members before Covid-19 report either a decline or absence of remittances since the pandemic began. They mostly cite loss of income from unemployment or decline in businesses for their supporting family members. The most affected are the elderly with some reporting going days without food.

Case study of Hellen

Hellen is a 52-year-old widow who survives on handouts. Her household comprises eight family members of one 25-year-old adult dependant and six child dependants (below 18 years old). She was recently evicted from the house of her late husband by her stepchildren. She is sickly and currently living with HIV/AIDS. When we met her, Hellen had not taken her HIV medication for several days due to hunger, she reported that she feels very dizzy when she takes the drugs without food. She reports that she has not eaten for a couple of days. Her sister, who used to send her monthly remittances of ZK500, cannot afford to send any more money because she was let go by her employer who had to downsize due to low production caused by Covid-19 restrictions.

“We only eat when someone helps out, otherwise we spend days without food, and we recently ate a few days ago. Our only focus is to fill our stomachs, the type of food doesn’t matter, and we, therefore, eat whatever we come across. Nutrition is a luxury; we are okay as long as we fill our stomachs. I am on antiretroviral treatment (ART) and I can’t even take my medication because it makes me feel so dizzy when I take on an empty stomach.”

“I have been sick throughout maybe it’s old age. I have also experienced some reduction in support from the people that were helping me because they are mostly traders whose businesses have been affected because of Covid-19 restrictions. They are not selling their products because of the restrictions. Money is really difficult to come by these days because my helpers are not making money.”

Closure of schools: The government closed down schools in March 2020 during the partial lockdown. Educational programmes were introduced on national television and radio stations as a mitigation measure. While some urban households report utilisation of these programmes, the rural households appear to have been left behind as a lot of households did not have access to televisions or radios. In comparison, some private schools were able to provide remote learning during lockdown, likely reinforcing already high levels of disparity between urban and rural households in the long term.

Reopening of schools: Schools reopened in February 2021, once they had the capacity to implement Covid-19 prevention measures. Social distancing in classes has however led to a reduction in contact hours for schools that have limited infrastructure. Schools with adequate infrastructure have managed to fully operate with usual contact hours.

“They have resumed physical classes, but their contact hours have been reduced in order to allow for social distancing amidst limited infrastructure.”

School dropouts: A lot of poor households struggled to send their children back to school after the reopening of schools due to loss of income which led to some children dropping out. Both rural and urban learners from poor households were affected. It was further reported that the school dropouts were leading to child labour for both girls and boys; early sex debut, transactional sex, teenage pregnancies and early marriages (especially for rural areas) for girls; and indulgence in drinking, smoking and criminal behaviour (such as robbery) for boys.

Case study of Hope

Hope is a 17-year-old girl who recently dropped out of school. Her parents divorced and she lives with her grandmother. Her parents are unable to sponsor her school fees and her grandmother failed to take her back to school after the Covid-19 partial lockdown. Hope is trying to raise school fees by selling cooked chicken pieces. She makes a ZK10 profit from each chicken and she manages to sell about three chickens per week. The challenge is that she is failing to save from her sales because most of the income is going towards daily subsistence at home.

Covid-19 awareness: Almost all people report some basic knowledge about how Covid-19 is transmitted and how transmission can be prevented. While some feel the Covid-19 statistics are exaggerated in order to solicit funds from donors, others feel that there is under-reporting due to limited testing and for the government to project a sense of social accountability for funded interventions. There are mixed feelings regarding the Covid-19 vaccine, with many people indicating hesitancy to be vaccinated.

Health care access: Fear of contracting Covid-19 and associated costs have deterred respondents from accessing health facilities. Others report that they prefer to self-medicate because they usually have to buy medicines due to stockouts at local health facilities. Some with Covid-19 symptoms fear visiting health facilities because they believe that most Covid-19 patients die when they go to the health facilities. This is mainly fuelled by sharing of false information. Some report that some clinical staff also discourage people from going to the health facilities by providing wrong information.

Increased cost of farm inputs: Farmers in rural areas report favourable rainfall during the current 2020/2021 farming season and are expectant of good harvests. Some farmers however fear reduced yields in relation to other years due to the increased cost of farm inputs which has limited their access to desired quantities of inputs.

Delay in delivery of inputs: The Ministry of Agriculture Fertiliser and Inputs Support Programme (FISP) provides vulnerable but viable farmers with subsidised inputs and fertiliser. Those on FISP however report continued delays in the delivery of inputs which often affects the yields of crops.

Increased cost of food: All households report an increased cost of food which has led to limited access to nutritious food. Poor households consider nutrition as a luxury and only focus on filling their stomachs. Farmers in rural areas are less affected as they produce most of their food (i.e., maize for mealie meal, groundnuts, potatoes, vegetables, livestock for meaty products and milk, and sunflower for cooking). Rural households also benefit from social capital and cohesion. The most affected include urban households, older people, and people with disabilities.

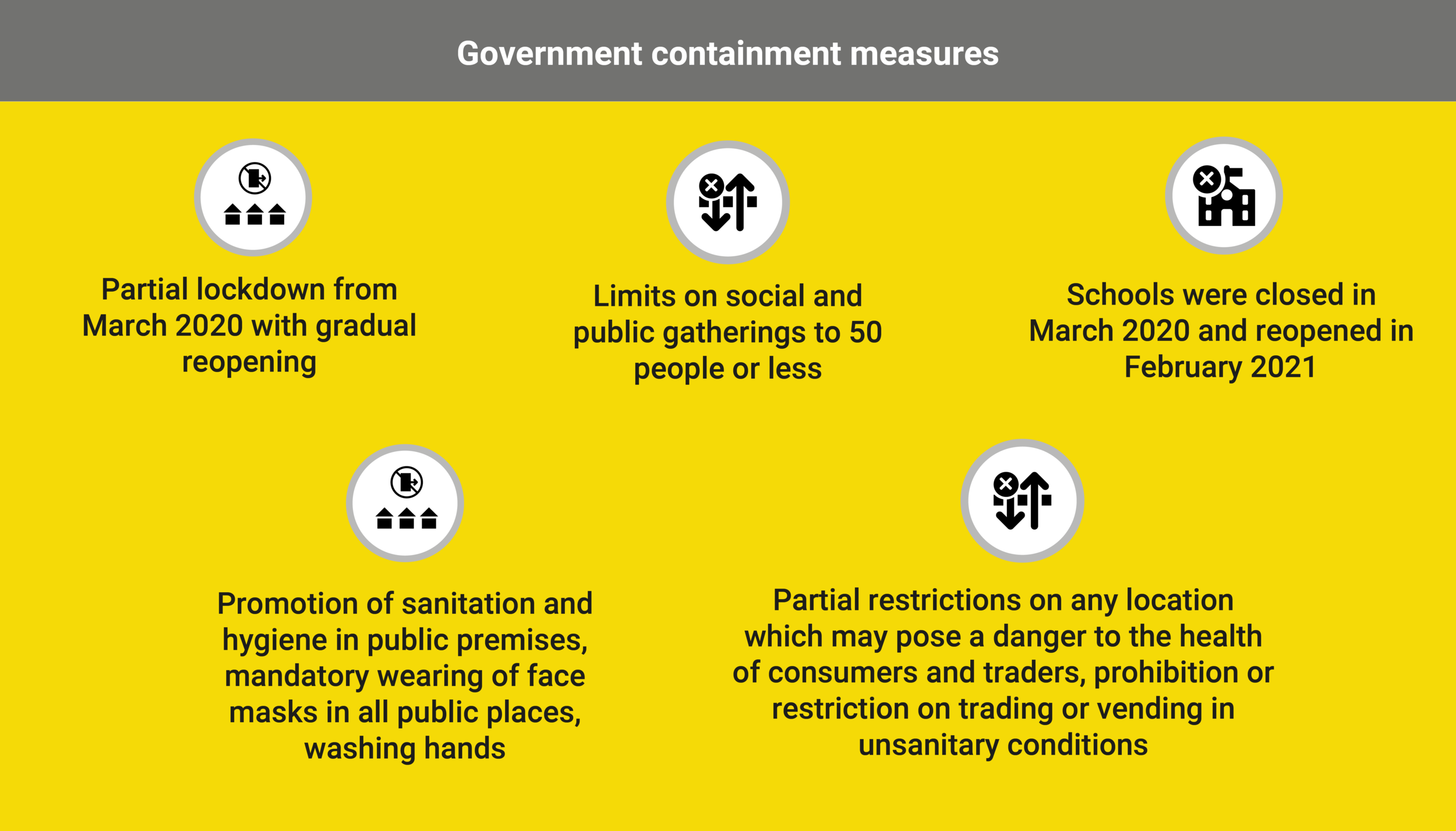

The government containment measures are guided by Statutory Instruments No 21 and 22 which were issued on 14 March 2020. See https://www.zambiahc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/SI-1.pdf, https://www.sh.gov.zm/?wpfb_dl=216 and https://www.moh.gov.zm/?wpfb_dl=145.

Coping Strategies

Food rationing and identifying cheaper sources: Several households report reducing the quality, quantity and/or frequency of meals as a coping strategy. Some also reported skipping a day without eating as a coping strategy.

“Avoiding wastage of food is very important. I ensure that cooking oil is reused, leftover food is consumed as long as it has not gone bad, and they put off the fire on the leftover charcoal and re-use it… We have managed to continue eating nutritious food because we buy from cheaper sources. You see, the cost of tomato is not the same in Shoprite and these local markets in the compound.”

Diversification of livelihoods: Multiple households report diversifying their sources of income in both rural and urban areas. However, this is most observed in sustained and temporary escapers. Some farmers are increasing their farming acreage and adopting farming as a business and many are venturing into gardening as an all-year source of income. Some non-farmers are also considering venturing into farming for food security. Most of those in business have either diversified or are considering diversifying their businesses.

Borrowing and drawing from savings: Many households reported failure to save and those with savings report drawing from their savings for daily subsistence. Increased borrowing was reported especially for payment of school fees. Those in savings groups (village banking) report borrowing for consumption as opposed to investment which was the norm prior to Covid-19. This is common among temporary poverty escapers and the sustained escapers in both urban and rural areas.

Support networks: Many respondents report receiving support to meet daily subsistence needs from family members, neighbours and ‘well-wishers’. Chronically poor households and older people who are unable to work or do not receive adequate social protection transfers report being highly dependent on support from their networks. Most of these respondents noted that their support networks were under strain due to reduced livelihoods, hence reduced remittances from kin networks. One older respondent in rural Chipata noted, for example, that his daughter in Lusaka had reduced income due to Covid-19 and was unable to provide the level of support that she normally provides to him and his wife to cover daily subsistence. As a result, they have reduced their quality and number of meals from three to one/two. Some urban respondents also report reduced support from their social networks.

Adherence to Covid-19 guidelines: Most respondents (especially those with businesses) report adherence to Covid-19 guidelines as a coping strategy to avoid loss of income and associated medical bills once exposed or infected with Covid-19. There is also a tendency by customers to patronise shops/trading areas where they feel safe.

Programmes in place to mitigate impoverishment due to Covid-19

Covid-19 relief fund: The Department of Social Welfare introduced a one-time ZK2,400 (about US$107) Covid-19 relief fund and a phone (SCT funds are channelled through mobile money transfers using phones). for each Social Cash Transfer beneficiary. Some people report that the provision of these funds as a lump has helped some beneficiaries to open micro-enterprises as a long-term mitigating measure against the impacts of Covid-19.

Other government support: The government has continued supporting the most vulnerable households that meet the social cash transfer criteria. All social cash transfer beneficiaries also received a one-time Covid-19 emergency cash transfer. Retirees also report continued receipt of their pension remittances and farmers have continued receiving subsidised inputs and fertiliser.

Key external sources

To find out more about the impacts of Covid-19 on poverty in Nepal, please explore the following sources that were reviewed for this bulletin:

This project was made possible with support from Covid Collective.

Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). The Collective brings together the expertise of, UK and Southern-based research partner organisations and offers a rapid social science research response to inform decision-making on some of the most pressing Covid-19 related development challenges.