Thank you for visiting our new Covid-19 Poverty Monitor. To find out more about the project, visit our blog about the project.

Areas of concern for the poorest and potential impoverishment

Poverty pathways key:

Chronic Poor (CP): those who have remained poor for at least 5 years.

Temporary Escapers (TEs): those starting off as poor five years prior to the study and later escape poverty and fall back into poverty.

Sustained Escape (SE): those starting as poor and later have a sustained escape from poverty (including those starting off as non-poor and sustain or increase their status.

Continued decline in wellbeing: Of the 28 people interviewed (comprising of 19 Chronically Poor (CP), 3 Temporally Escapers (TEs), and 6 Sustained Escapers (SEs)), most of them reported a continued decline (n=20) in wellbeing during the period March to June 2021. Only four of the surveyed households reported an improvement in wellbeing while the other four indicated no change in wellbeing. The recorded improvement in wellbeing is largely attributed to increases in business activities due to a decline in new Covid-19 cases between March and May 2021, and therefore fewer restrictions. The change can also be linked to the cessation of electricity rationing (load shedding). However, all surveyed households anticipate a decline in wellbeing due to the current third wave of Covid-19 and heightened containment measures to reduce further spread of the virus.

“My daughter used to sell vegetables at the market, but she had to stop because of poor business. The number of people coming to buy reduced a lot. She then decided to start selling in town on the corridors where the council confiscated all her vegetables, that is how my business collapsed because I had used all the money for orders.” Female urban participant, Kabwe

Table 1: Change in the wellbeing of participants between rounds 1 and 2 of interviews

Loss of livelihoods and income: Most people reported a loss of income mainly due to continued partial loss of livelihoods. While micro and small business owners report being able to conduct business, their income has reduced. Although this is partly because of declining economic performance due to the huge contracted national debt, it can also be attributed in part, to inflation and stark changes in foreign exchange rates. The year-on-year inflation rate for March 2021 was 22.8%, increasing to 24.6% for July, representing a 1.8% difference between March and July 2021. This implies that the prices of goods increased by 22.8% and 24.6% between March 2020 and March 2021 and between July 2020 and July 2021 respectively (see Zambia Statistical Agency Monthly Bulleting Volumes 216 and 220).

“There is a lot of change; my profit has gone down but I am still doing the same business: selling doormats. These days, I only sell one or two doormats in a month. Things are bad; people don’t have the money, I make about K20 (US$1.03) or K40 ($2.07) per month.” Female urban respondent, Kabwe

“I am still struggling with my business, it keeps declining… My income has gone down because it’s very difficult to sell these days and I can go for three to four days without selling anything. Most of the people have electricity, and my expenditure has gone up because things are very expensive. For example, an egg used to cost K1 ($0.05). Now it’s K3 ($0.15). My expenditure is increasing while my income is going down.” Female urban respondent, Lusaka

“I stopped selling buns because my customers started getting on credit and when it’s time to pay, they would always give me stories, so I decide to stop.” Female rural respondent, Chipata

Increased household expenditure: All respondents reported an increased cost of basic items with exception of mealie meal, cooking oil, vegetables and rain-fed crops. Price reductions for cooking oil were facilitated by the government while price reductions for mealie meal, vegetables and rain-fed crops are largely attributed to seasonality.

“The cost of living has gone up because prices of all the commodities you can mention are going up every day. For example, we used to buy bread at K9 ($0.46) now as we are speaking it’s at K17 ($0.88). Even a tray of eggs, last time you came it was at K25 ($1.29) and now it’s at K55 ($2.85) so really my expenditure has changed.” Male urban respondent, Lusaka

“From the last time we spoke, my income has gone down yet my expenditure is going up every day. The cost of living has gone up and our economy is very bad.” Female rural respondent, Chipata

Increased cost of conducting business: Micro and small businesses reported an increase in the cost of conducting business due to an increase in order prices of goods without a corresponding increase in selling price.

“There is a reduction in our income and an increase in our expenditure because my business is not doing well – because of the increase in order prices of commodities. Life has become expensive.” Female urban respondent, Kabwe

Partial loss of remittances: Some respondents report partial loss of remittances due to a continued decrease in the level of support from their relatives. Support has declined because supporters are also struggling for survival due to continued decline of income and loss of livelihoods.

“My income has reduced because the money I used to receive from my son has reduced.” Female rural respondent, Chipata

“I still do farming and get help from my granddaughter, although the help is not as often as before because she is also saying her business is going down, she is only making about K800 ($41.45) to K1,000 ($51.81) per month.” Female rural respondent, Chipata

“There are some changes since the last time we spoke: my daughter who used to give us K250 ($12.96), now only sends us K50 ($2.59) occasionally.” Female rural respondent, Chipata

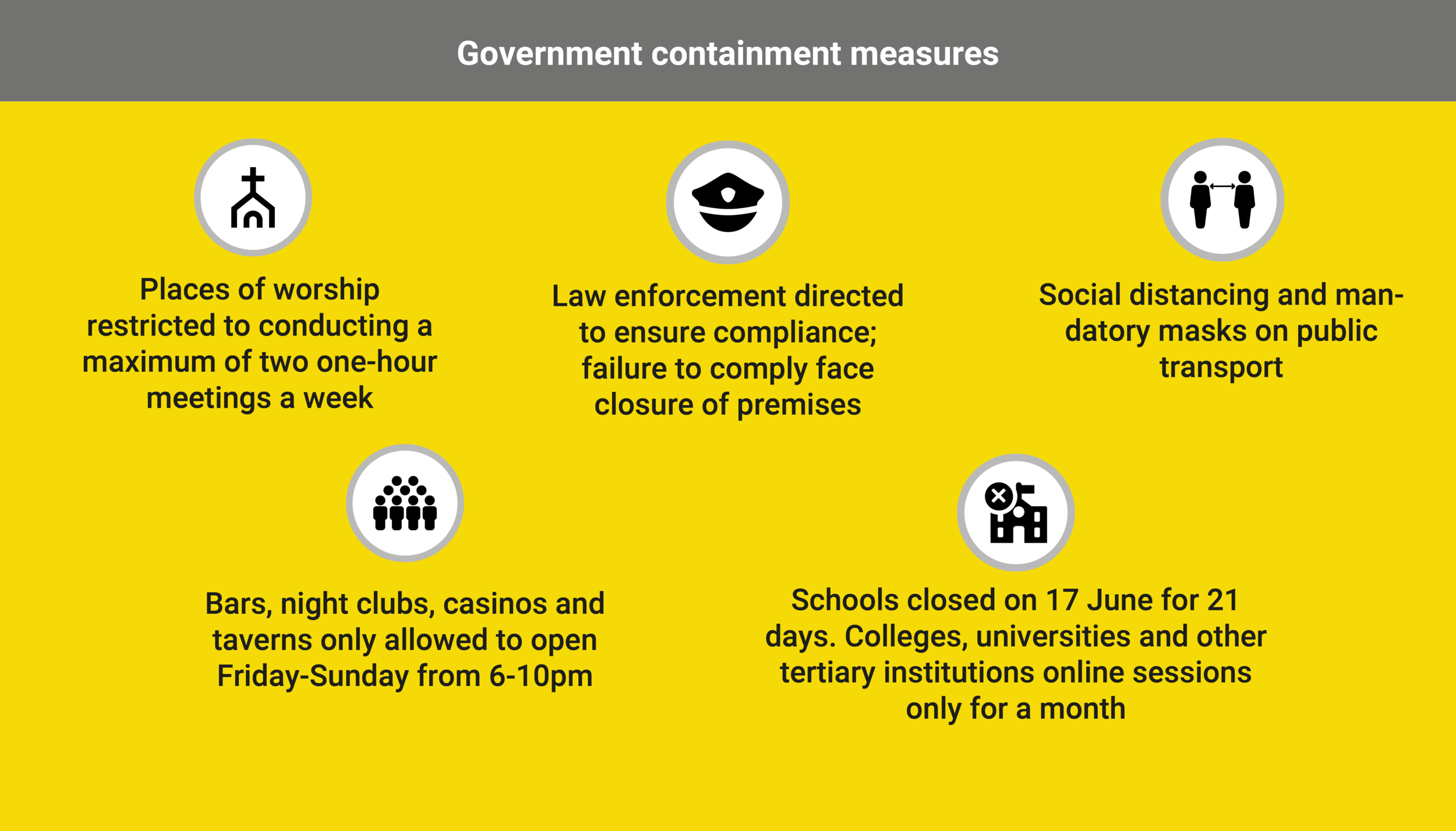

School closures: The government closed schools from 17 June to 16 August 2021 due to a third wave of the pandemic. Some schools continued supporting pupils and students online while other learners with access to television depend on the public educational broadcasts by the Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation (ZNBC). However, these measures were not effective due to limited access in both rural and urban areas. Most of the surveyed households in rural areas did not have access to television sets, radios or the internet and those that had were constrained by lack of awareness of such educational programmes, lack of electricity and internet access. The main limiting factor in urban areas was the limited awareness of these programmes.

“I am not aware of any educational programmes that are broadcast on radio or television. We are just waiting for the schools to open. How can we know when I don’t even have a radio, even this phone I am using to talk to you is for the community caregiver.” Female rural participant

“I have a television and a radio which I connect to solar power, and I once heard that there are educational programmes on radio and television. The problem is that I do not know the time they broadcast. The other problem is that I use solar because we are not connected to the national power grid in this village. We only watch the television in the evenings for a few hours due to limited power.” Male rural participant

“Last time I mentioned I have someone in university, the one I said was on bursary. They closed due to Covid-19, and he was saying that his friends are learning through the computer so he asked me to help him buy one, but I could not manage because I do not have that kind of money, even if he had a computer, I am not sure I can manage to be buying him internet bundles.” Female urban participant

Access to health services: Respondents report increased access to health services than in the last bulletin. There is reported improvement in health-seeking behaviour for people with Covid-19 related symptoms despite the reported limited bed spaces and oxygen cylinders. Participants say medication for Covid-19 patients is continually out of stock, which is synonymous with a constrained health service delivery system. As a result, some people prefer to self-medicate with over-the-counter drugs and traditional remedies rather than going to health facilities. While stock-outs are common in both rural and urban areas, a lack of bed space and oxygen cylinders are more prevalent in urban areas.

Covid-19 vaccination: The Covid-19 vaccine is still associated with various myths; some religious people associate it with a Christian prophecy (666: the mark of the beast), while others see it as a tool devised by the west to depopulate Africa. However, there has been an improvement in the number of people willing to be vaccinated since the last bulletin. A total of 496,594 people had their first vaccination and about 193,603 have been fully vaccinated.

Access to staple foods: Most rural respondents report having enough staple food, although the research was conducted during the harvest period. However, some report poor yields due to limited agricultural inputs. Most of those in urban areas report continued limited access to staple food.

A reduction in the quality of food was common to both rural and urban areas. The reduction in the price of mealie-meal, cooking oil, vegetables and rain-fed/seasonal crops appears to have little impact due to the continued decline in people’s incomes.

“As it is the harvest season, food is available and [we keep] most of it for home consumption. We have harvested our crops now and food is plenty.” Male rural respondents, Chipata

“We have not secured much food this year due to a poor harvest caused by limited farming inputs.” Female rural respondent, Chipata

“I have no food; I depend on my neighbour. We only eat once a day, as having two meals would mean spending the next day without food. We cook our supper at around 4pm then that’s it for a day because we can’t afford to buy food for two meals as my business is not doing well.” Female urban respondents, Lusaka

“In terms of food, there is great reduction because I no longer have proper food. I eat whatever is available and I rarely have food in my house. I mostly eat once a day. The quantity is less and the quality of the food very poor.” Female urban respondent, Kabwe

“We no longer buy food in bulk. We depend on pre-packed mealie meal which we buy every time we want to have nshima. Sometimes, we buy more food if the business is doing well.” Male urban respondents, Kabwe

Social cohesion: Covid-19 restrictions continue to limit social cohesion. Restrictions not only limit social interactions but also weaken the informal social support systems in the communities as there are limited opportunities for meeting and assisting each other. This has adversely affected vulnerable groups that survive on these support systems, such as the elderly, disabled and female-headed households.

“Now we can’t even have weddings or kitchen parties. it is our tradition to go with presents and the community contribute money during these functions, helping new couples a lot with material and financial support from the community. Support which one cannot receive if they just married without the activity. And the support received increases when more people are in attendance.” Urban female participant, Kabwe

“I don’t receive many visitors now because of Covid-19. Community members and relatives previously used to come around to see me, they would even fetch me water, clean my surroundings and mostly come with food. Now I do not see them as often because people are not allowed to move.” Female rural participant, Chipata

Stigmatisation: Former and current Covid-19 patients report stigmatisation; people tend to stay away from Covid-19 patients long after they recover. This often leads to loss of business when the affected is a businessperson.

“I have been sick with Covid-19 three times now. The first time I had Covid-19, I had serious challenges, my workmates stopped socialising with me even after I recovered. Some are still scared of me even now. Sometimes I even feel like Covid-19 is the reason my contract was not renewed. This has really affected my carpentry business because I think potential customers are scared to visit. This has also affected my wife who is a marketeer because people who know her are still scared to buy from her, over two months after I recovered from Covid-19.” Male urban participant, Kabwe

Coping Strategies

The respondents report the following coping strategies:

Drawing on savings and borrowing: A few participants who are resilient report being able to save during good times and draw on savings or borrow during hard times.

Limiting expenditure to essential commodities: Most participants report reduced expenditure on non-essential commodities.

Government remittances, e.g., social cash transfer and pensions.

Informal trade: Some participants have taken up informal trading, mostly in their households as a coping strategy.

Farming and gardening: Some urban participants report taking up farming and gardening as a means of reducing expenditure on food.

Casual day labour: Some participants reported taking up casual labour in addition to their usual livelihood activities, a copy strategy they often turn to during hard times.

Food rationing.

Informal support networks including family, friends and well-wishers.

Identifying of cheaper sources of commodities such as buying vegetables directly from farmers.

Prayer: Some report that they pray and wait for God to provide.

Programmes in place to mitigate impoverishment due to Covid-19

Covid-19 Emergency Cash Transfer: The government continues to disburse the ZK2,400 ($20.74) one-off Covid-19 relief fund for those on the social cash transfer (SCT) programme. Five of the households interviewed that are social cash transfer beneficiaries confirmed receipt of the funds.

Key external sources

To find out more about the impacts of Covid-19 on poverty in Nepal, please explore the following sources that were reviewed for this bulletin:

This project was made possible with support from Covid Collective.

Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). The Collective brings together the expertise of, UK and Southern-based research partner organisations and offers a rapid social science research response to inform decision-making on some of the most pressing Covid-19 related development challenges.